Writing as Conveyor Belt

The book I’m currently writing deals, on one level, with gun violence. It’s foremost a novel, of course, and I’d like the story and the characters to come first, before any of my opinions, my facts and figures, my strongly held beliefs. But this, it turns out, is quite difficult. It feels, at times, almost impossible.

How do I infuse my story with undercurrents of deeper thought and careful considerations, even, possibly, offer a cultural commentary of sorts, without being overly obvious? Preachy and didactic. It’s a delicate line.

Verlyn Klinkerborg says this:

“If you love to read -- as surely you must -- you love being

wherever you find yourself in the book you’re reading,

Happy to be in the presence of every sentence as it passes by,

Not biding your time until the meaning comes along.

Writing isn’t a conveyer belt bearing the reader to “the point” at the end

of a piece, where the meaning will be revealed.

Good writing is significant everywhere,

Delightful everywhere.

To study this in more depth, I’ve revisited two books. One that does what I’m attempting to do really well and one that doesn’t quite hold its toes on the right side of the sanctimonious line and falls, more often than not, into conveyor belt writing.

For this post, I’ll focus on the first book, the one that does it well, as I feel certain most of us have read and can call to mind (several?) books like the second.

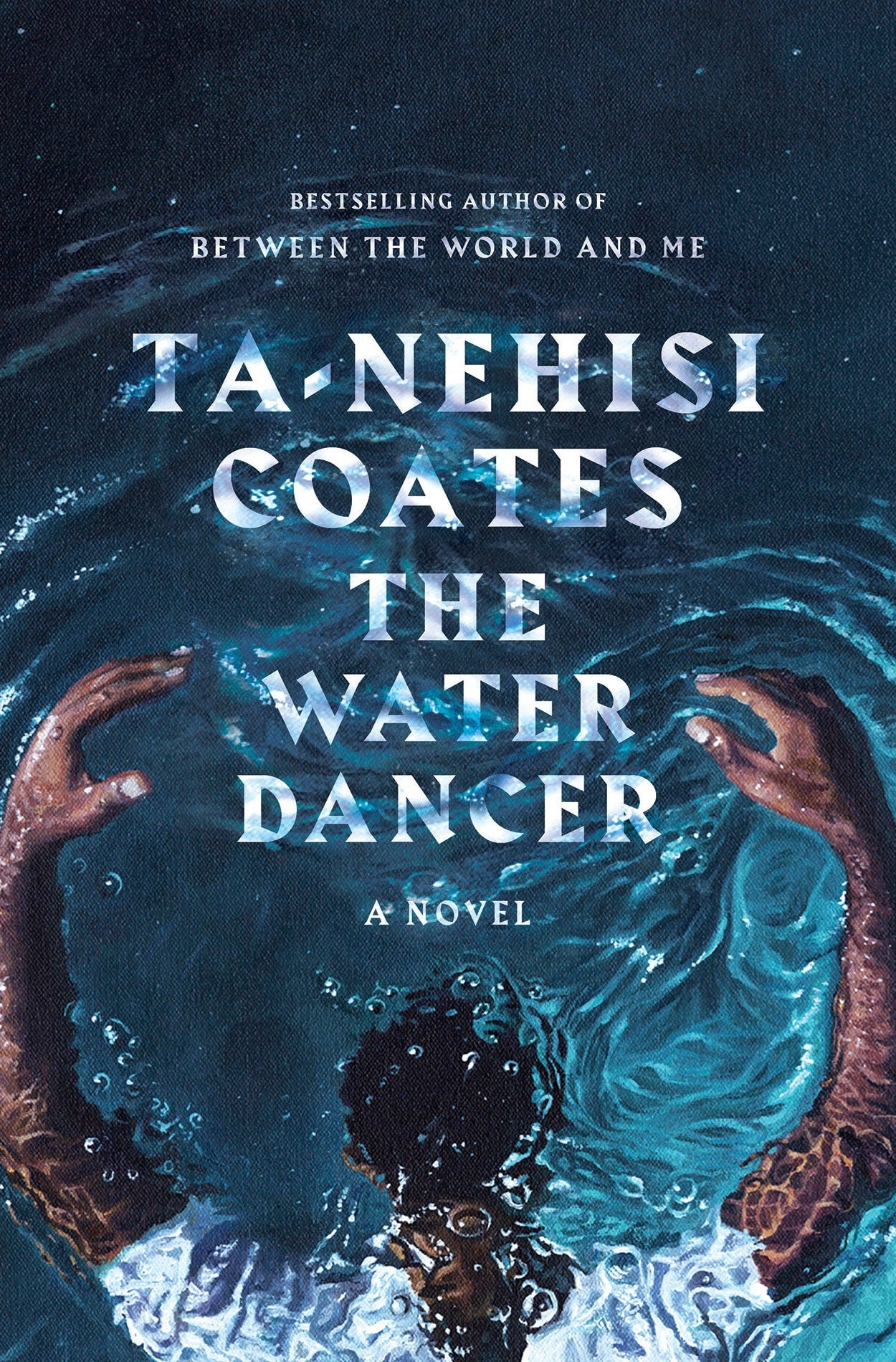

THE WATER DANCER by Ta-Nehisi Coates manages to convey “meaning” but the reader hardly notices. Or rather the reader is so carried away by the beauty and significance of the prose, it’s only later, after putting the book down, that they reflect on what would rightly be considered “the meaning.”

The following is perhaps the best example of prose that serves first to enchant the reader regardless of “where it’s going” or what it “means.”

Walking down the back stairs, I knew my father’s statement could only be reconciled through the peculiar religion of Virginia -- Virginia, where it was held that a whole race would submit to chains; Virginia, where this same race held the math that molded iron and carved marble. . . where a man would profess his love for you one moment and sell you off the next. Oh, the curses my mind constructed for my fool of a father, for this country where men dress sin in pageantry and pomp, in cotillions and crinolines, where they hide its exercise, in the down there, in a basement of the mind, in these slave-stairs, which I now descended, into the Warrens, into this secret city, which powered an empire so great that none dare speak its true name."

They key, it seems, if one is to use Coates as an example and Klinkenborg’s words as guide, is to focus first and always on the prose. This passage from THE WATER DANCER is incredible. It’s only two sentences (!) but Coates infuses so much in such a short span. How does he do it?

First, he uses anaphora multiple times, which is the repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of successive phrases, clauses, or sentences to convey urgency or emotion.

“Virginia, where it was held that a whole race would submit to chains; Virginia, where this same race held the math that molded iron and carved marble. . . where a man would profess his love for you one moment and sell you off the next.”

“… in the down there, in a basement of the mind, in these slave-stairs, which I now descended, into the Warrens, into this secret city…”

He also offers us a master class in alliteration.

“held the math that molded iron and carved marble…”

“Oh, the curses my mind constructed for my fool of a father, for this country where men dress sin in pageantry and pomp, in cotillions and crinolines…” (anaphora in here, too!)

There’s a lot more to enjoy and unpack in those two sentences but I’ll stop there for now.

So, does it mean something? Coates does more in those two sentences to tenderly expose what it “means” when men align themselves with systemic power structures and the frustration, despair, grief, rage and sorrow felt by a people who’ve been held perpetually under the white man’s boot than some books accomplish in an entire volume. Two sentences!

It’s not necessary for Coates to grasp the reader’s hand and drag them to the end where the “meaning” sits in wait. His prose delights and disarms, animates and enthralls and the meaning manifests without any glaring signposts. Whether the reader acknowledges it or not, agrees with it or not, hardly matters. Because, if they’re like me, they’ll simply love being wherever it is they find themselves in Coates’s writing, “happy to be in the presence of every sentence as it passes by.”

Honestly, when I read those sentences, it’s hard not to feel like giving up. I mean, compared to Coates and his cotillions and crinolines, why bother? It’s a high standard, is what I’m saying. So here’s to us, writer friends, as we press on. As we focus first on our prose. May it delight and disarm, enthrall and entice, infused at every turn of phrase with wonder, meaning, significance and splendor. See you next week.

On my bookshelf

Behold the Dreamers by Imbolo Mbue

These Precious Days by Ann Patchett

The Hurting Kind by Ada Limón

Gentle Writing Advice by Chuck Wendig

Recently finished

The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store by James McBride

Wellness by Nathan Hill

The Berry Pickers by Amanda Peters

Recent Posts

Top 5 Books of 2023

On Descriptions & Third Drafts

Long Sentences & the Bombardment of the Moment

Brevity & Brian Doyle