On Weasels and Writing

Sometimes, rather than discuss one craft element and examine it from the vantage point of various texts, it can be helpful to read one text as a whole, in its entirety, and then look at what the piece is doing. How does it do it? What does it evoke?

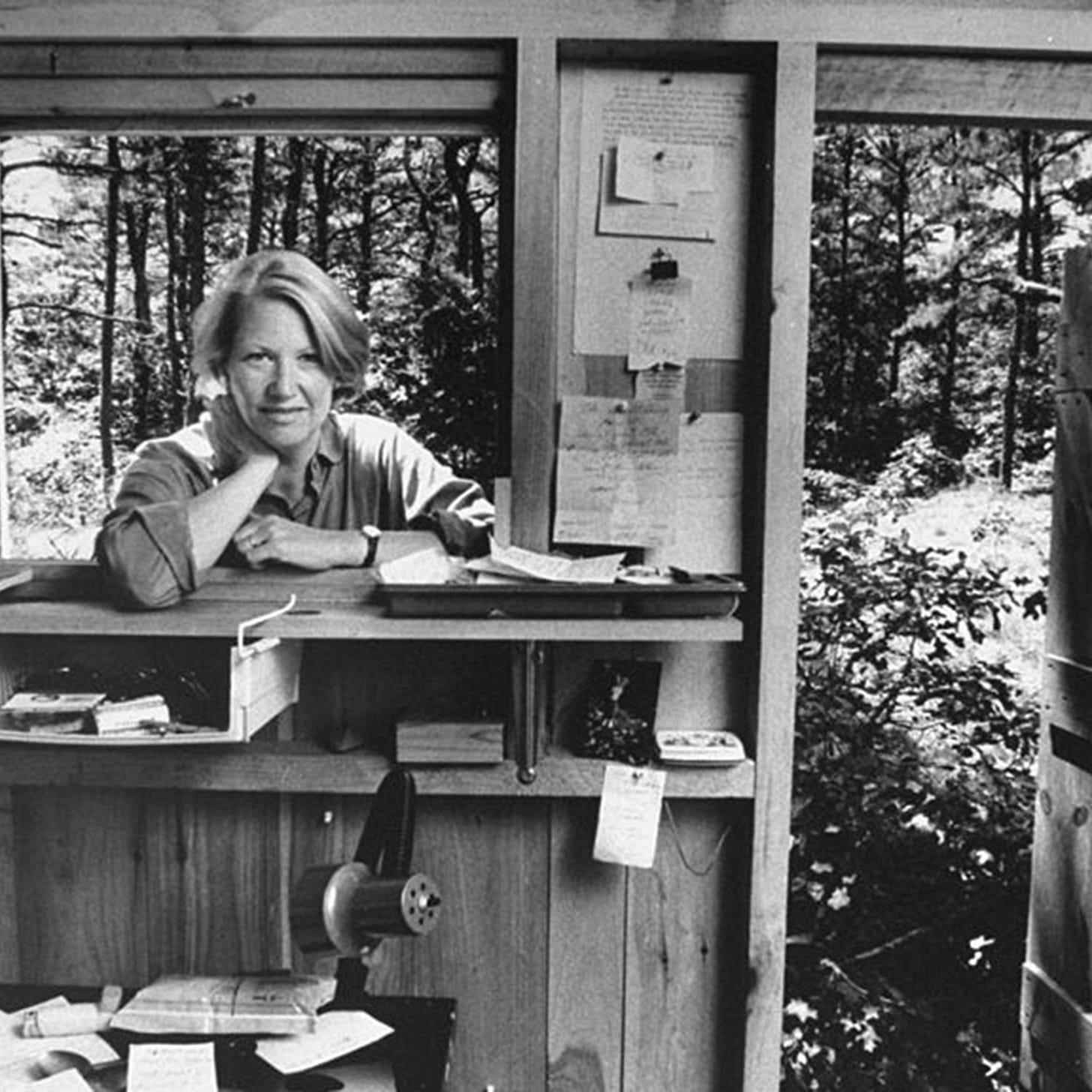

In this context, here on substack, it would obviously be difficult to look at an entire novel together. But how about this? Let’s look at LIVING LIKE WEASELS by Annie Dillard. It’s short. Should only take 5-10 minutes to read the whole thing.

Go take a look and meet me back here.

It’s good, right? One of my favorites. And there are obviously a lot of different ways we could look at it; different angles from which we could assess, approach, analyze, appreciate. I thought, for this experiment, it would interesting to look at it through the lens of Klinkenborg’s admonishment against writing as a conveyor belt (refresher here).

From the opening line all the way through to the end, Dillard wants to show us something. Clearly she intends to teach, to have us “arrive at meaning.” But the essay never bows under the weight of didacticism. It’s neither preachy nor over the top and yet the reader is, by the end, enticed to notice their world anew, possibly even reorient their entire lives to do so.

So how does Dillard do it? I think the answer is found, at least in part, in the pacing. Dillard divides the piece into six parts and she takes her time. She establishes a relationship with her reader that builds and builds with each successive section so that by the end of the essay the reader is willing to go anywhere Dillard wants to take them.

Part 1

The first portion of the piece is devoted to expository facts about weasels. Mostly we learn that weasels are tenacious. Stubborn. Once they latch onto something they don’t let go. Dillard ends the first section with the story about a man who shot an eagle out of the sky and discovered the skull of a weasel still clamped onto its throat.

Part 2

In the second section Dillard explains why she’s telling the reader about weasels in the first place— “I have been reading about weasels because I saw one last week”— and she sets the scene by explaining where she is. She’s at Hollins Pond near Tinker Creek not five minutes from civilization. “There’s a 55 mph highway at one end of the pond, and a nesting pair of wood ducks at the other. Under every bush is a muskrat or a beer can.” She shows us the sacred and the profane of the space she occupies. The ordinary and the extraordinary. We all know places like this.

Part 3

The third section is the climax. The encounter with the weasel. “Weasel!” she says simply, opening the third section, immediately bringing the reader to her place of surprise, wonder, awe.

Our look was as if two lovers, or deadly enemies, met unexpectedly on an overgrown path when each had been thinking of something else; a clearing blow to the gut… It emptied our lungs. It felled the forest, moved the fields, and drained the pond.

The reader is breathless, stock still, waiting with Dillard. Wondering what, if anything, will break the reverie.

And because Dillard brought the reader so gently along, explaining the species, setting the scene, recounting the moment of ecstasy with the weasel, the reader is primed now to hear Dillard’s deeper thoughts. We’re ready, eager even, to understand how her encounter connects to our own lives, and our collective experience.

Parts 4-6

The fourth section -- very brief -- is where Dillard responds to the encounter. She does so by expressing her own desire to learn from the weasel.

I would like to learn, or remember, how to live… I don’t think I can learn from a wild animal how to live in particular -- shall I suck warm blood, hold my tail high, walk with my footprints precisely over the prints of my hands? -- but I might learn something of mindlessness, something of the purity of living in the physical senses and the dignity of living without bias or motive.

Because Dillard is telling us what she would like to do, rather than what we ought to learn, we’re free to ponder Dillard’s response from a distance. Then, when she switches in the fifth section from first person to first person plural, and moves seamlessly between the two, saying, “We could live under the wild rose wild as weasels, mute and uncomprehending. I could very calmly go wild,” we’ve been primed. We’re ready to join her there. “We could, you know. We can live any way we want,” she tells us.

It’s here, at the end of the fifth section — what Klinkenborg would call “the meaning.” We’ve arrived at “the point of it all.” It’s brief, Dillard’s admonishments to “stalk your calling in a certain skilled and supple way.” She makes her point succinctly, almost casually, and her writing is truly, as Klinkenborg puts it, “significant everywhere, delightful everywhere.” The reader is breathing “yes,” even as they are already moving on to the sixth and final section of the essay.

Dillard closes by switching tense yet again, this time from first person plural (“we”) to second person, now addressing her reader directly. “I think it would be well, and proper, and obedient, and pure, to grasp your one necessity and not let it go, to dangle from it limp wherever it takes you.” Here she circles back to the story she told at the beginning about the eagle with the weasel skull embedded in its neck. And we, her readers, are ready now to take flight, to fly aloft with her without hesitation, to “let [our] musky flesh fall of in shreds, and let [our] very bones unhinge and scatter, loosened over fields, over fields and woods, lightly, thoughtless, from any height at all, from as high as eagles.”

Here’s to us, writer friends, as we learn from Dillard and her weasel; as we learn, or remember, how to live; as we hold on for a dearer life. Til next week.

On my bookshelf

THE RIVER WE REMEMBER by William Kent Krueger

GENTLE WRITING ADVICE by Chuck Wendig

STOLEN FOCUS by Johann Hart

ZERO AT THE BONE by Christian Wiman

Recently finished

THE HURTING KIND by Ada Limón

FATES AND FURIES by Lauren Groff

BEHOLD THE DREAMERS by Imbolo Mbue

THE HEAVEN & EARTH GROCERY STORE by James McBride

Read anything interesting lately? I’m always looking for recommendations. I’d particularly like a poetry rec, as I just finished Limón’s collection.

Recent Posts

George Saunders & Large White Cats

Writing as Conveyor Belt

Top 5 Books of 2023

On Descriptions & Third Drafts